Observing Diffuse and Planetary Nebulae

Follow the tips below to maximize your planetary viewing experience.

1. Nebulae Basics

M 20 the Trifid Nebula showing all 3 types of nebulae. Pink emission nebula (right), Blue reflection nebula (left), and dark nebulae in front of the pink emission nebula.

Nebulas are collections of gas and dust that exist within and between galaxies. There are three main types of nebulae, emission, reflection, and dark.

Emission nebulae are ionized regions of glowing gas that emit light at particular wavelengths depending on which gases are ionized. The two brightest emissions from nebulae in visible light are from ionized hydrogen and oxygen.

Reflection nebula are collections of gas and dust that are not ionized but rather reflect the light of bright nearby stars. Reflection nebulas as a result have a characteristic white glow with blue hues, reflecting the broadband emissions of stars. Blue hues in reflection nebulas are most common when reflection nebulas are part of star-forming regions where the radiation is dominated by bright young blue stars.

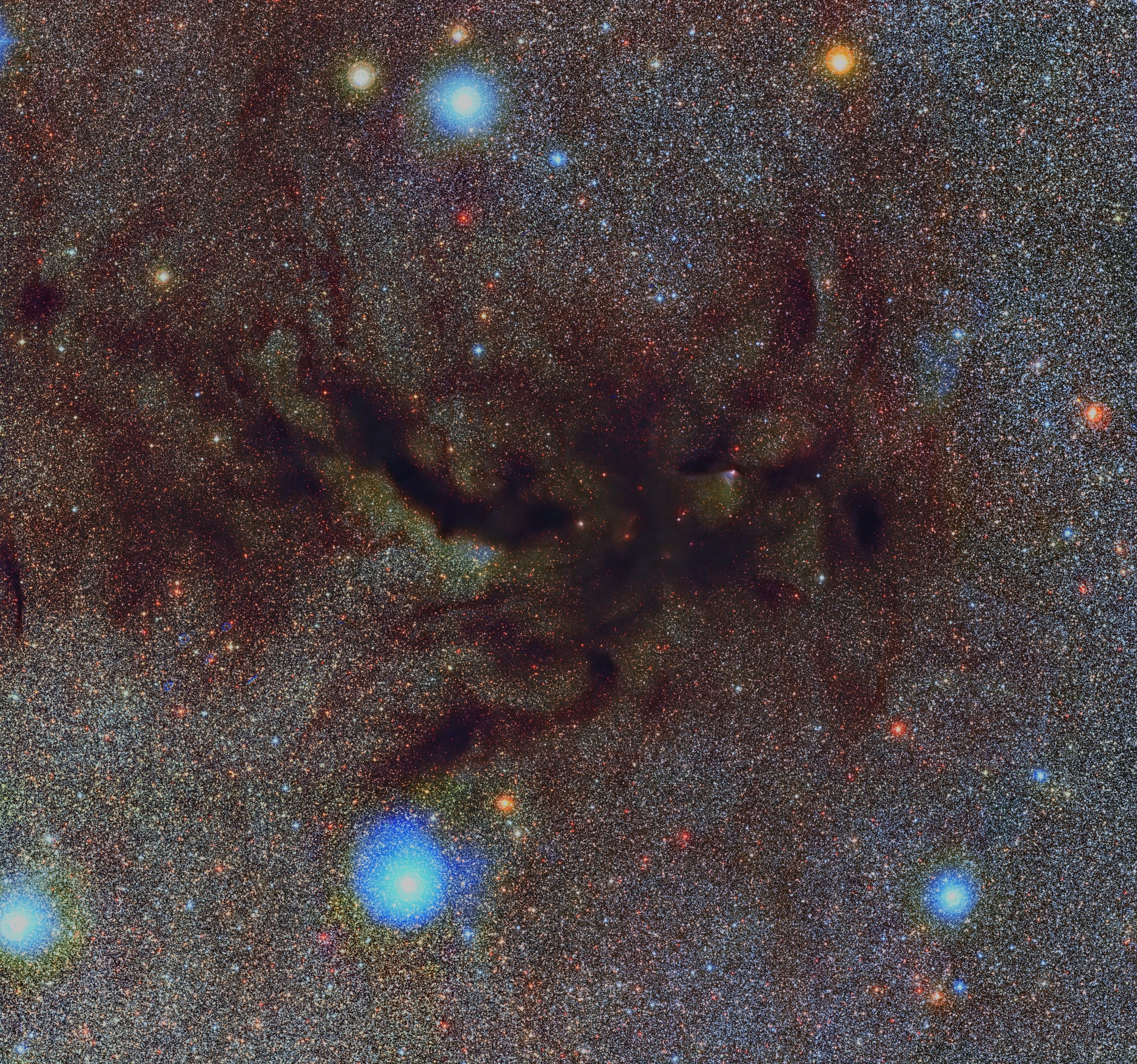

The last type is dark nebulae. Dark nebulae are gas and dust lying along the line of sight of farther background stars and light-emitting nebulae. Their gas and dust absorb the light making them appear as dark lanes against the background sky.

The lines between these categories of nebulae are just like the nebulas themselves, nebulous and hard to define. All three types can appear in one object such as the Trifid Nebula (M 20) and even the darkest dark nebulae reflect some light, revealing brown and orange tones with sufficiently deep imaging.

2. Emission Nebulae and Star Birth

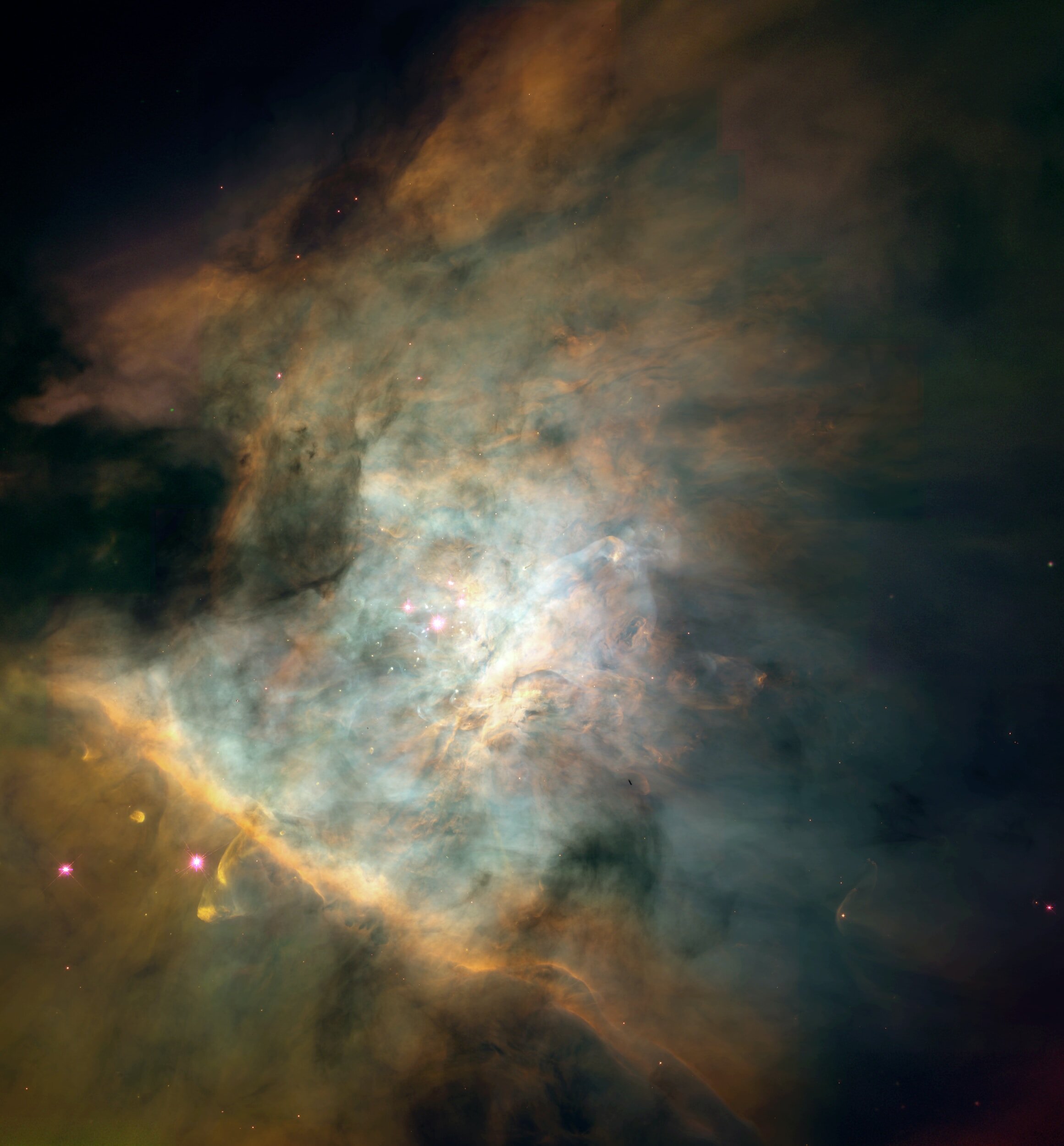

A true color image of the Orion Nebula with its bright central regions glowing green, not red.

The largest nebulae are star-forming regions where clouds and dust have collapsed and are in the process of making stars. These star-forming regions create stars of across a wide range of masses, from tens to hundreds of solar masses to objects that are barely stars at 8% the mass of the Sun. The most commonly formed stars are small red dwarf stars with the stellar classification of K and M. The most massive stars called O and B-type stars are the rarest and most luminous.

The hydrogen gas within these star-forming regions can only be ionized in visible wavelengths by the massive O and B-type stars causing the gas to emit red light referred to as hydrogen-alpha at 656 nm. The most energetic of these stars have enough energy to ionize oxygen gas causing light to be emitted in three more energetic green emission lines, referred to as oxygen-3, between 501 and 493 nm. The stars more energetic still cause hydrogen to be further ionized and emit a blue-green glow at 486.1 nm called hydrogen-beta.

Most emission nebulae are red and pink in images but would actually appear very green to the eye if our eyes were sensitive enough. The sensitivity of the eye peaks in the green near the oxygen-3 emission, and is only 25% as sensitive at the red wavelengths of hydrogen-alpha emission. Emission nebulas however tend to emit far more hydrogen-alpha than oxygen emission enabling the ionized hydrogen regions to be equally if not more visible.

Emission nebulae that are most visible to the eye have ionized oxygen, and emission nebulae with minimal oxygen emission are harder to see.

3. Planetary Nebula, Supernova Remnants, and Star Death

M 57 the Ring Nebula, a planetary nebula in Lyra with ionized hydrogen on the outside surrounding a central region of ionized oxygen.

Not all emission nebulae are a result of star-forming regions, but instead are the result of a star in its final stages or the leftovers of a violent death. These two types of nebulae, planetary nebulae, and supernova remnants, are not usually called emission nebulae due to their distinct intrinsic and visual properties.

Planetary nebulas are the result of a sun-like star in its final moments, ejecting its outer layers into space. The majority of planetary nebulae in the sky are small and bright, appearing as a ghost of a planet. Their appearance and not their properties are what give them their name. The first ejections are mostly ionized hydrogen with a characteristic red-pink glow. The latter ejections consist more of ionized oxygen with a green glow. The gradual ejection of material leads to well-structured spherical or dual-lobed nebulae. These ionized gas ejections only last for a few thousand years and a planetary nebula will fade over tens of thousands of years as the ejected gas dissipates.

The largest stars do not fizzle away like sun-like stars but explode violently in supernova explosions. Stars with 8 times the sun’s mass or larger are likely to go supernova at the end of their lives. Supernovae often leave behind remnants from their explosions and in contrast to planetary nebulae are not well structured. They often are asymmetric and consist of many finely structured filaments of gas. Supernova remnants are also hydrogen and oxygen-rich and unlike planetary nebulae do not have distinct disparate regions of varying composition. The gas is well mixed and the use of various filters will reveal different parts of the nebula in the same region.

4. Using Filters to Improve Contrast

Emission nebulas whether they are star-forming regions, planetary nebulae, or supernova remnants, consist of ionized gas that has line emission. All elements emit and absorb light of very particular wavelengths from their electrons dropping or jumping in energy levels. These electron transitions are what cause the ionized gas to absorb and emit light and result in their glow. For a detailed understanding of filters and filter usage refer to the deep dive on Everything Astronomical Filters.

The three particular emissions of interest for observation in the visible spectrum are hydrogen-alpha (Hα), oxygen-3 (O-III), and hydrogen-beta (Hβ). To increase the contrast of a nebula against the background sky, the broadband glow of the sky needs to be suppressed without removing the light from the nebula of interest. A UHC (Ultra-High Contrast, sometimes also called a nebula booster) allows for the light from all 3 emissions of interest (Hα, O-III, and Hβ) to be transmitted restricting all other wavelengths. A UHC filter is best used on nebulae with prominent Hα emission. UHC filters come in various transmission bandwidths and the narrower the bandpass the more selective and higher contrast the filter is. A typical UHC filter has bandpasses between 50-20 nm in width. The narrower the filter the dimmer the view becomes and the more being dark-adapted is essential.

The Eastern Veil Nebula with and without an O-III filter

Narrowband filters are as their name suggests, filters with narrow transmission bandpasses. Typical narrowband filters used for visual observing are between 12 and 6 nm wide. Imaging usually uses even narrower 3 nm bandpasses. Hα narrowband filters are popular and very effective for imaging but since the human eye is not very sensitive at Hα wavelengths is not recommended for visual observing. The most commonly used narrowband filter for visual is O-III and it can work wonders in light polluted skies. The combination of the high sensitivity of the human eye to oxygen emission and the narrow bandpass of an O-III narrowband filter can make nebulae invisible without it, stand out with one.

Hβ filters are used on very few objects such as the Horsehead, and California Nebula, and are often nicknamed Horsehead nebula filters being purchased to specifically view the Horsehead Nebula. Hβ filters are best used in very dark skies on a few objects.

5. Reflection and Dark Nebula

The reflection nebulae of M 45, faint strands of dark nebulae, and the surrounding IFN of the Pleiades bubble.

Reflection and dark nebulae are very difficult to see and nearly impossible to view from bright light-polluted skies. Reflection and dark nebulae are broadband targets that glow or obstruct light equally across all wavelengths of the visible spectrum. With the adoption of LED streetlights, light pollution is also broadband so no filters can be used to isolate light from these objects and restrict light from light pollution. Dark skies are a must without exception.

If you are trying to see reflection nebulae, view from a Bortle 5 sky or darker, and go to the darkest skies possible to try to see dark nebulae. Dark nebulae can be seen from brighter skies if they are backlit by bright emission nebulae such as in M 20 the Trifid Nebula.

The only emission nebula I have been able to see from a typical Bortle 7 sky is M 78, a reflection nebula near the Orion’s Belt. M 78 appeared as a faint smudge barely visible against the background sky glow in Bortle 7 but from a Bortle 5, almost Bortle 4 sky, M 78 is bright and obvious.

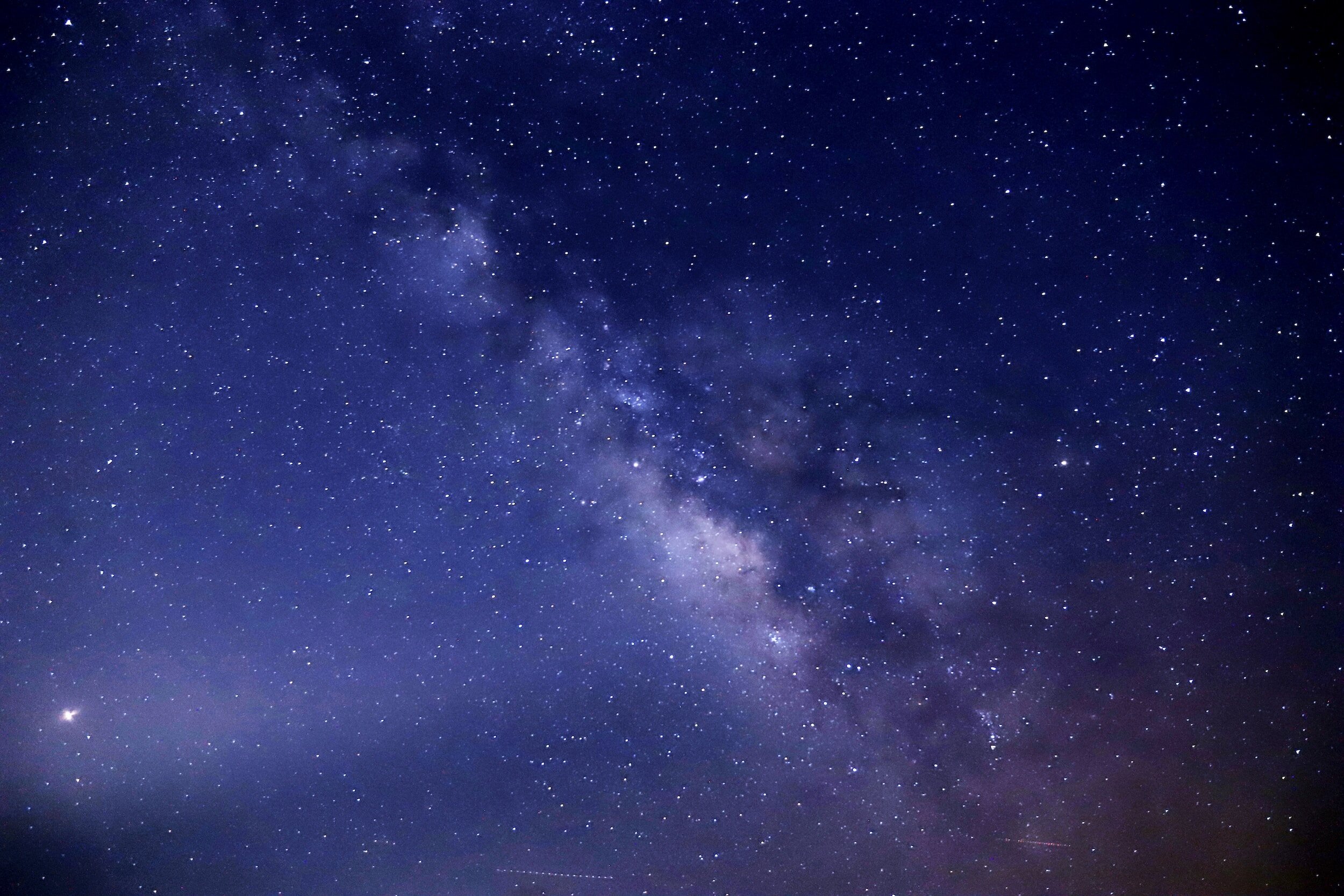

The largest dark nebulae can be seen as dark patches in the Milky Way where the glow from the galaxy fades away. From bright suburban skies, their effects can be seen with binoculars or low magnifications in a telescope by sweeping across the Milky Way. Rich starfields will fade to star-poor regions quickly as the view passes over the dark dust lanes caused by dark nebulae.

6. Notable Nebulae

The following nebulae are some of the biggest, brightest, and most unique. The biggest take up multiple degrees in the sky, the brightest can be seen naked-eye in a dark sky and some even in light polluted skies, and the most unique have peculiar recognizable shapes. The list starts from the biggest and brightest and progresses to smaller and fainter nebulae.

Most nebulae below have an eyepiece recreation that best represents what they appear like from bright suburban skies. Some nebulae are too faint to see from bright suburban skies and have eyepiece recreations for suburban-rural transition skies. All nebulae will have a filter listed that they are best viewed with. These recreations represent the view when the object is high in the sky, and an actual view may be dimmer when the object is low. The views are also made assuming the viewer has had at least 3 minutes to dark adapt. If the listed objects are viewed with no dark adaptation or while looking at lights, the object will appear much dimmer than recreated.

To make the eyepiece recreation as realistic as possible set the screen brightness to the highest setting and lower it until the 8 rectangle is barely visible. A dark sky will provide much better views in comparison to the eyepiece recreations and is always recommended.

Eyepiece recreation screen calibration aid

Best and Brightest

These are the best and brightest nebulae the night sky has to offer. All of these nebulae are visible from bright suburban skies and become jaw dropping in truly dark skies.

Unique and Odd

These are the not the brightest nebulae in the sky but are very interesting objects to observe.

Faint Fuzzies

These are all the nebulae that are not the best, brightest, or unique. Every nebula is different and these are for those of you who want to see as much and as deep as you possibly can. Objects will be added to this list every few months as I observe more nebulae and make eyepiece recreations. These are ordered from easiest to hardest to see.

Orion Nebula

Messier 42 / NGC 1976

Magnitude: +4.0

Type: Diffuse Emission Nebula

Observing Months: November - April

Aperture: Naked eye

Filter: UHC / O-III / H-Beta

Size: 45 Arcminutes

Distance: 1340 ly

M 42 is the brightest star-forming region visible from northern latitudes. The nebula's core is visible to the naked eye even in heavy light pollution. In brighter skies only the brighter core regions of the nebula are visible. In darker skies, the nebula fills the eyepiece at low magnifications (30x).

A UHC filter improves contrast in the nebula, making the gas's details easier to see. In sufficiently dark skies keen observers can see hints of green and pink around the nebula's core.

Due to the large size of M42, a larger exit pupil (4+) is recommended. High magnification is not needed.

Ring Nebula

Messier 57 / NGC 6720

Type: Planetary Nebula

Magnitude: +8.8

Observing Months: May - November

Aperture: 70mm+

Filter: UHC / O-III

Size: 3 Arcminutes

Distance: 2300 ly

M 57 is one of the best and brightest planetary nebulae in the Northern sky. It has a high surface brightness allowing it to be easily visible in light-polluted skies. Larger apertures do improve views even in light-polluted conditions. A UHC filter improves the contrast between the nebula and the background sky. For telescopes with apertures larger than 16 inches or for 8 or 10-inch telescopes in dark skies an O-III filter is preferred over a UHC.

This nebula like most planetary nebulae does well at high magnifications. An exit pupil of 2 or larger is reccomended.

Swan Nebula

Messier 17 / NGC 6618

Type: Diffuse Emission Nebula

Magnitude: +6.0

Observing Months: May - October

Aperture: Naked eye or Binoculars

Filter: O-III / UHC

Size: 20 Arcminutes

Distance: 4990 ly

The Swan Nebula also referred to as the Omega Nebula is one of the best nebulas in the night sky. A large majority of this star-forming region consists of ionized oxygen allowing it to be easily visible to the eye.

In smaller telescopes only the brighter central swan shape is visible and with larger telescopes, the surrounding gas begins to fade into view. In a dark sky with a large telescope, the entire field of view is filled with swirls of gas and dust far past the central bright region.

An O-III filter works best in ideal conditions but a UHC may provide a better view in poor seeing conditions. Use low magnifications and the largest exit pupil possible. Exit pupils of 4 mm and larger are recommended.

Dumbbell Nebula

Messier 27 / NGC 6853

Magnitude: +7.4

Type: Planetary Nebula

Observing Months: May - November

Aperture: 100mm+

Filter: O-III / UHC

Size: 6.7 Arcminutes

Distance: 1200 ly

The Dumbbell Nebula is the largest planetary nebula of its surface brightness in the entire night sky. M 27 is one of the closest planetary nebula and is a stage of development where it is large in size and still retains a high surface brightness. As it continues to develop it will fade away into the surrounding galactic region.

The majority of the light emitted by planetary nebula is from ionized oxygen and the dumbbell nebula is no different. This nebula benefits most from an O-III filter but a UHC can provide a better view of the structures in the ionized hydrogen. In sufficiently dark skies the “wings” of the nebula can be seen with the use of an O-III filter.

M 27 has a lower surface brightness than most planetary nebula and is best seen at low magnifications and large exit pupils. An exit pupil of 3 mm or larger is recommended.

Lagoon Nebula

Messier 8 / NGC 6523, NGC 6533

Magnitude: +6.0

Type: Diffuse Emission Nebula

Observing Months: May - October

Aperture: Naked eye or Binoculars

Filter: O-III / UHC

Size: 55 Arcminutes

Distance: 6490 ly

The Lagoon Nebula is visible to the naked eye as a fuzzy patch in the Milky Way in sufficiently dark skies and can easily be seen with binoculars from city skies. The nebula is known for its prominent dark dust lane that crosses the middle of its bright core.

Adjacent to the brightest part of the nebula is an open cluster easily seen with telescopes, NGC 6530.

This nebula quickly appears when imaged but can appear rather faint in the eyepiece. In a dark sky M 8 easily fills the eyepiece, but from a suburban sky only the brightest parts are visible. A UHC filter can help make the nebula pop out against the background and an O-III filter will improve contrast between the main dust lane and bright core.

Large exit pupils and narrowband filters are recommended. An O-III filter with an exit pupil over 4 mm will provide the best results.

Carina Nebula

NGC 3372 / Caldwell 92

Magnitude: +1.0

Type: Diffuse Emission Nebula

Observing Months: March - August

Aperture: Naked Eye

Filter: UHC / O-III

Size: 120 Arcminutes (2°)

Distance: 8000 ly

The Carina Nebula is the most impressive nebula in the entire sky. It is over 4 times visually larger and brighter than the more famous Orion Nebula since it is only visible from southern skies.

Similar to the Orion Nebula, the bright core of the nebula is visible to the naked eye even from city skies. With a telescope, more of the nebula begins to be revealed, including a multitude of open star clusters that have recently emerged from nearby regions.

A UHC filter helps the nebula stand out against the background sky and an O-III filter aids in seeing the large dust lanes in the center of the nebula. In a dark sky, this nebula shows color as green and pink hues in the brightest regions of ionized gas.

Eastern Veil Nebula

NGC 6692 / Caldwell 33

Type: Diffuse Emission - Supernova Remnant

Magnitude: +7.5

Observing Months: May - October

Aperture: 50mm+

Filter: O-III

Size: 60 Arcminutes (1°)

Distance: 1470 ly

The Eastern Veil Nebula, also called the Network Nebula, is the brighter part of the Veil Nebula complex. All parts of the Veil Nebula are the leftovers or an exploding star that has undergone a supernova explosion and thrown its guts into space.

Supernova remnants are messy turbulent regions of ionized gas and dust and unlike planetary nebulas do not have regions that vary drastically in composition. An O-III filter is essential to see this nebula from suburban skies it may only appear as a ghostly wisp. Wait for the clearest most transparent nights to see this nebula.

As large of an exit pupil as possible should be used and an eyepiece with high-quality low-reflection coatings can make a huge difference.

Western Veil Nebula

NGC 6960 / Caldwell 34

Type: Diffuse Emission - Supernova Remnant

Magnitude: +7.5

Observing Months: May - October

Aperture: 50mm+

Filter: O-III

Size: 60 Arcminutes (1°)

Distance: 1470 ly

The Western Veil Nebula, also called the Witche’s Broom Nebula, is the the counterpart to the slightly brighter Eastern Veil. This part of the Veil is slightly harder to see when centered but easier to find as the naked eye visible star 52 Cygni sits centered in front of the gas.

Just like the Eastern Veil an O-III filter is essential to see this nebula from suburban skies it may only appear as a ghostly wisp. Wait for the clearest most transparent nights to see this nebula.

As large of an exit pupil as possible should be used and an eyepiece with high-quality low-reflection coatings can make a huge difference.

Messier 78

NGC 2068

Type: Reflection Nebula

Magnitude: +8.0

Observing Months: November - April

Aperture: 100mm+

Filter: None

Size: 8 Arcminutes

Distance: 1600 ly

Messier 78, sometimes called Casper the Friendly Ghost, is the brightest reflection nebula in the sky. Reflection nebulas are broadband objects and do not benefit from the addition of filters. A very broad light pollution filter such as a CLS filter may help improve views.

M 78 appears as two slightly brighter than the background sky glows with the dimmer of the two being the adjacent nebula NGC 2071. Wait for a very clear moonless night and use the lowest magnification possible. Slightly increasing the magnification may help increase contrast by reducing the background sky glow.

From a dark sky, the dark dust lane around the reflection nebula can easily be seen as the extended nebulosity fills the eyepiece.

Hubble’s Variable Nebula

NGC 2261 / Caldwell 46

Type: Reflection Nebula

Magnitude: +9.0

Observing Months: November - April

Aperture: 100mm+

Filter: None

Size: 3 Arcminutes

Distance: 2490 ly

Hubble’s Variable Nebula named after Edwin Hubble who extensively studied it, is a peculiar reflection nebula in Monoceros the Unicorn. The nebula is about one light-year long and is believed to be caused by an outflow of gas from the star R Monocerotis.

Being a reflection nebula, filters do not improve views and a clear moonless night is needed. More of the nebula is revealed in darker skies.

Exit pupils between 2-3 mm are best to reduce the sky background and maintain the surface brightness of the nebula.

Blinking Planetary Nebula

NGC 6826 / Caldwell 15

Type: Planetary Nebula

Magnitude: +8.8

Observing Months: May - October

Aperture: 150mm+

Filter: O-III / UHC

Size: 36 Arcseconds

Distance: 5200 ly

The blinking planetary nebula is an easy-to-observe planetary nebula in Cygnus. NGC 6826 is visible in small telescopes but a large aperture is recommended to reveal more detail in the nebula.

Without a filter in medium-size telescopes, staring directly at the central star causes the surrounding beula to disappear. However, when averted vision is used the nebula reappears. This behavior gives the blinking planetary nebula its name.

In large telescopes or with an O-III or UHC filter, the nebula remains easily visible against the background sky.

Even with the use of an O-III narrowband filter, high magnification and exit pupils are 1-2 mm are recommended.

Saturn Nebula

NGC 7009 / Caldwell 55

Type: Planetary Nebula

Magnitude: +8.0

Observing Months: July - December

Aperture: 150mm+

Filter: O-III / UHC

Size: 35 Arcseconds

Distance: 4300 ly

The Saturn planetary nebula is a pretty jewel of an object lying in the zodiacal constellation Capricornus. The Saturn nebula as its name suggests, appears similar in shape to the planet Saturn but with a ghostly nebulous appearance.

The central regions are easily seen without a filter and the use of an O-III filter helps make the ansae that gives this nebula its name, pop!

In 2022 the planet Saturn sat close in the sky to the nebula and did so for part of 2023 as well.

As with most planetary nebulas high magnification and small exit pupils are best. An exit pupil of 1-2 mm is recommended.

Ghost of Jupiter

NGC 3242 / Caldwell 59

Type: Planetary Nebula

Magnitude: +7.7

Observing Months: February - June

Aperture: 150mm+

Filter: O-III / UHC

Size: 64 Arcseconds

Distance: 3600 ly

Brighter than the famous Ring Nebula M 57, the much less famous Ghost of Jupiter is bright enough to show color in dark enough skies and large enough telescopes. Low in the sky from mid-Northern latitudes, not easily found, and not present in the Messier catalog, this impressive object has stood far from fame.

The Ghost of Jupiter is similar in size and shape to the planet Jupiter in most telescopes with its inner details requiring larger apertures to see and resolve. Telescopes 8 inches and larger should be able to see a two-shelled structure with the use of an O-III filter, being able to distinguish between the inner and outer regions.

As usual with planetary nebulas, high magnification and small exit pupils are recommended. exit pupils between 1-2 mm are best.

Eagle Nebula

Messier 16 / NGC 6611

Type: Diffuse Emission Nebula

Magnitude: +6.0

Observing Months: May - October

Aperture: 50mm+

Filter: UHC

Size: 35 Arcseconds

Distance: 5690 ly

The Eagle Nebula may be the most famous nebula in the night sky. The Eagle Nebula contains the famous picture taken by the Hubble Space Telescope of the Pillars of Creation. This nebula despite its claim to fame is surprisingly difficult to visually observe.

This star-forming region emits almost entirely in red Hα light from ionized hydrogen, a wavelength of light the eye is not very sensitive to. The human eye is very sensitive to green light and all of M 16’s nebulosity disappears when imaged with a green filter.

Darker skies are needed to see any nebulosity within M 16 at all and extremely dark skies are needed to see the outer extensions of the nebula.

Use a UHC filter in combination with low magnification for the best views.

Trifid Nebula

Messier 20 / NGC 6514

Type: Diffuse Emission, Reflection, Dark

Magnitude: +6.3

Observing Months: May - October

Aperture: 50mm+

Filter: None / UHC-E / CLS / UHC

Size: 20 Arcseconds

Distance: 5200 ly

The Trifid Nebula has all three main types of nebulae, emission, reflection, and dark. The Trifid’s nebula name however does not come from having three types of nebulae but for the three spoked dust lane in the heart of the emission region. Truthfully I see more than three spokes when observing this nebula but telescopes have come a long way since its discovery.

This nebula needs darker skies to be seen and may not be visible at all from bright suburban skies. The emission region of M 20 benefits from a UHC filter and helps bring out details in the dust lanes. A UHC filter also makes the reflection nebula appear to disappear and can be a fun thing to try out in dark skies. Truly dark skies are needed to see the full extent of the wisps of the reflection nebula.

Low magnifications and large exit pupils are recommended.

Helix Nebula

NGC 7293 / Caldwell 63

Type: Planetary Nebula

Magnitude: +7.3

Observing Months: August - December

Aperture: 50mm+

Filter: UHC / O-III

Size: 18 Arcminutes

Distance: 693 ly

The Helix Nebula is often referenced as the eye of god or the eye of Sauron due to images of the nebula having a striking resemblance to a human eye. Its name however comes from a helix-like appearance when observed visually.

The helix nebula is the largest in apparent size of all known planetary nebulae and is one of the closest to the Earth. The nebula however is in its final stages and has partially faded away into the surrounding interstellar space. As a result, this nebula has a very low surface brightness and is a challenge to observe. Dark skies and narrowband filters are a must to observe this famous nebula, with both UHC and O-III filters working well.

With an angular size over 60% the size of the full moon, very low magnifications and large exit pupils will provide the best chance of observing the Helix.